“A los que lo vieron, pero lo tienen olvidado; a los que no lo pudieron presenciar, pero sienten la curiosidad de saber cómo sería y a los que ya no podrán conocerlo por estar en desuso o prohibido”

Gabriel Flores Garrido

Cronista Oficial de Vera

LA MATANZA DEL CERDO

“A los que lo vieron, pero lo tienen olvidado; a los que no lo pudieron presenciar, pero sienten la curiosidad de saber cómo sería y a los que ya no podrán conocerlo por estar en desuso o prohibido”. Includes English version at the end (elaborada por Francisco Javier Martínez Castro).

oooooooo0000000ooooooooo

No sé de ningún animal que, como el cerdo, despierte tanta controversia a la hora de decidir la conveniencia o no de tratarlo como alimento. Por un lado, para la civilización occidental, su carne y vísceras son objeto casi de veneración, hasta el punto de recibir el tratamiento de “exquisitez alimenticia”. Sin embargo, la cultura oriental, especialmente judíos y musulmanes, tienen prohibido su consumo y, en muchos casos, sienten rechazo incluso por su contacto, al considerarlo un animal impuro. Si estableciéramos un segmento de alimentación podríamos ubicar su carne en los dos extremos del mismo: en un lado se agruparían los que aseguran que del cerdo se aprovechan “hasta los andares” (tal vez refiriéndose a sus pezuñas, protagonistas de exquisitos platos) y, en el otro, los que no quieren tener ningún contacto por la relación que establecen entre el animal y el carácter contaminado y turbio que le achacan.

Monumento al Cerdo en La Alberca, Salamanca

Trataremos en este comentario o crónica lo que nos afecta con más cercanía y, por tanto, está más próximo a nuestra costumbre y cultura.

Quizá muchos de los que hayan comenzado a leer esta “crónica porcina” se pregunten el motivo de ella. La causa no es otra que las fechas que vivimos; es cierto que en este mes de noviembre concurren otros dos hechos de gran significación que podrían tratarse en importantes crónicas: uno de carácter general como es el día de Todos los Santos, además de la dedicatoria y recuerdo de nuestros difuntos, y otro de ámbito más local como la destrucción de Vera por el devastador terremoto del 9 de noviembre de 1518; de ambos se ha hablado mucho y largo, así pues, he optado por una imagen y costumbre ya perdidas de las que, además, trataré de recordar y aprender, aunque espero que la añoranza no dañe mi ánimo ni el de los que vivieron esos momentos ya perdidos, y que estas líneas les obligarán a mirar atrás hacia un punto ya tan lejano.

Siempre, el día de san Martín (próximo 11 de noviembre) fue considerado como la apertura de la temporada de matanza del cerdo, aunque dependía de la zona y, especialmente, de lo fría que fuera esta y del tiempo que se mantuvieran las bajas temperaturas. Todo el año se había estado engordando al cochino para que fuera el alimento familiar durante una larga temporada; de hecho, existen numerosos refranes alusivos a la fecha, incluso uno de ellos: “a todo cerdo le llega su san Martín”, con una maligna doble intención que cada cual sabe desdoblar según con quien hable y el motivo que en ese momento se trate.

Es cierto que, en ocasiones, un motivo de regocijo y fiesta para unos es desgracia para otros; creo que la matanza del cerdo es uno de los ejemplos más claros.

Recuerdo los días de matanza como algo extraordinario, muy distintos a los del resto del año. La jornada comenzaba temprano con los hombres que iban a participar en la “faena” alrededor de una botella de anís, para tomar una copa que ya formaba parte del ritual y parecía imprescindible antes de remangarse para comenzar el rito.

Cuchillo de matarife propiedad de Pedro Contreras Salas. Principios del siglo XX

No transcurrían muchos minutos cuando se dejaba oír el gruñir del cerdo tratando de escapar de las manos que, como tenazas lo apresaban de cualquier parte de su cuerpo para subirlo a la mesa y, una vez arriba, atarlo para que el matancero pudiera hacer su trabajo con más comodidad y mayor seguridad, aunque no creo que al pobre animal le importara mucho, ni lo uno ni lo otro, y si hubieran tenido la capacidad de pensar seguro que no habrían dedicado ni un segundo a facilitar la labor a quien lo iba a degollar. Vera ha tenido buenos y certeros matarifes; no es que sea algo de lo que vanagloriarse pero, si lo vemos desde el punto de vista de que quien gruñía encima de aquella mesa iba a servir para mitigar las necesidades alimenticias de buen número de paisanos, posiblemente lo veríamos desde otra perspectiva.

Hasta entonces el cerdo había tenido una vida plácida: comer, dormir y volver a comer era su ciclo de vida.

Morillo. Nuestro protagonista

En una casa de la parte baja de la calle de la Plata mi familia engordó algunos cerdos que mi padre casi llegaba a “humanizar” hasta el punto de ponerles nombre. Recuerdo con especial “humor y ternura” a “Felipe” y “Morillo”, no sé el porqué de sus onomásticas pero, además de tener sus propios nombres, los sacaba a pasear por el tramo bajo de la calle y caminaba junto a ellos hasta donde hoy está el banco de Santander. Allí charlaba un rato con el “tío Juan”, un guarda que había en la finca que hoy es la urbanización Alcaná, mientras los cerdos hociqueaban el suelo pacientemente hasta que, concluida la conversación entre mi padre y el guarda, volvían lentamente a casa. Utilizaremos a “Morillo” como el triste y sacrificado protagonista de esta crónica.

Como digo, durante un año, aproximadamente, y si la memoria no me falla, todo era placidez, felicidad y buena vida para los gorrinos; tan buena les resultaba que, en ocasiones, alcanzaban los 200 kilos o incluso los superaba.

Aproximadamente dos semanas antes se compraban las especias o “recao”, término que desconocía; así denominaban al conjunto de matalhúva, pimentón, tomillo, etc. que previamente había que limpiar porque solían venir acompañadas de pequeñas piedras, que se disimulaban con la propia especia para aumentar el peso de esta y así sacar mayor beneficio de su venta. La picaresca hispana siembre presente.

Fotografía extraída de: entredosamores.es/campodecriptana

Llegado el “día de autos” todo era muy distinto para el cochino, su vida placentera tocaba a su fin: se colocaba en el centro de la calle la mesa ya mencionada. Entre cuatro o cinco hombres, una vez atrapado ”Morillo”, (al que ya hemos adjudicado el papel de “actor principal”) era fuertemente sujetado del rabo por uno de ellos, otro lo hacía del hocico una vez atado para evitar mordiscos, y otros dos de algunas de las patas, orejas o de donde pudieran asirse. No era tarea fácil porque el animal luchaba, pateaba y se agitaba con brío intentando librarse de lo que parecía sospechar. Su agitación aumentaba en intensidad y fuerza al sentir el cuchillo en la garganta y, al poco, el pataleo iba disminuyendo según la sangre brotaba de su cuello y era recogida en un lebrillo mientras la removían pausadamente evitando así que se cuajara e hiciera una madeja, como le llamaban a las hebras que se formaban. La sangre recogida era utilizada para entripar morcillas y embutidos. Existía la creencia de que si esta labor de agitar la sangre era realizada por mujeres que estuvieran en período menstrual, se malograban no solo las morcillas sino toda la matanza.

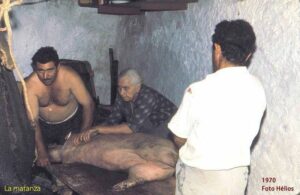

Escaldando el cerdo. Imagen de Helios. Propiedad de Sebita Flores.

Esos minutos, que hoy nos parecen, y son, de una crueldad fuera de toda duda, eran presenciados por una fila de niños que, sentados en la acera, contemplábamos atónitos, imagino que producto de una mezcla de miedo y sorpresa, con los ojos abiertos sin pestañear, y sin mirar a ningún sitio que no fuera el cuerpo inerte del pobre animal, al que escaldaban con agua hirviendo para, una vez rasurado, poder aprovechar la corteza de su piel. Supongo que si alguna capacidad de sorpresa nos quedaba a los niños la perderíamos al ver el escaldado del pobre animal poniéndonos en su piel (pocas veces esta expresión será mejor empleada); aunque, por otro lado, poco le podía importar ya a “Morillo” ser rociado con agua hirviendo, su sufrimiento ya estaba cumplido.

El cerdo era colgado cabeza abajo de una traviesa de madera de olivo, normalmente, que recibía el nombre de camal, al que se sujetaba colgándolo de lo que en la anatomía humana correspondería al tendón de Aquiles. En esta situación se le abría el vientre para extraer vísceras, tripas y demás despojos, porque todo es aprovechado en la anatomía de un cerdo. Se tomaban unas muestras de su carne en distintos puntos de su cuerpo que el veterinario analizaba con el fin de evitar la transmisión de alguna enfermedad, especialmente la triquinosis, que, aunque no es inevitablemente mortal, a veces, puede serlo. La toma de muestras y su análisis daba lugar a la pillería, especialmente en las matanzas realizadas en cortijos y lugares apartados, donde el hecho no llegaba a conocimiento del veterinario: nunca faltaba el bribón de turno que amenazaba con decirlo si no recibía una compensación (otra vez la picaresca hispana llevada a la práctica).

Imagen propiedad de María Jesús Cazorla Núñez

Las mantecas que “forraban” interiormente su vientre se desprendían de este y se separaban con una caña quedando el animal abierto en canal, evitando el contacto entre sí para impedir que tomaran un olor característico de resultado poco agradable.

Antes del reparto de la cata se habían entripado los embutidos: las morcillas se cocían en una caldera, previamente lustrada con arenilla, y colocada sobre un trébedes, que en esta zona llamábamos estrebes, por deformación de la palabra (algo que en nuestra tierra hacemos frecuentemente).

El día siguiente, muy de mañana, y tras la correspondiente copa de anís, procedían al despiece del pobre “Morillo”, que había permanecido toda la noche colgado del camal esperando ser convertido en el alimento de varios meses, aunque la duración, lógicamente, dependía del número de miembros de la familia.

Este segundo día era todo un emblema de la matanza y uno de los momentos más esperados: LAS MIGAS. En una sartén gigantesca la harina era removida constantemente hasta quedar bien desgranada, abriéndose un hueco en el centro para albergar los “tropezones” (tocino frito, hígado y morcilla troceados, pimientos y trozos de carne magra) que se cubrían y mezclaban con las migas recuperando el calor que habían perdido en la espera. A partir de ahí, como una mesa redonda, todos estaban dispuestos para, poniendo una nota de humor, “meter la cuchara y dar un paso atrás”, como quedó acuñada la frase; de no cumplir esa condición, era tal el número de comensales que, pese al gran tamaño de la sartén, no todos se habrían podido acercar al calor de la migas y al sabor de los tropezones.

Otro momento inevitable de la matanza era el reparto de la cata ofrecida a amigos y allegados que, generalmente, consistía en un trozo de tocino, un par de morcillas y un hueso de espinazo; de ello, nos ocupábamos los más pequeños, que siempre mostrábamos interés en entregar las catas porque, con frecuencia, tenía su recompensa en forma de algunas pesetas, que siempre venían bien.

Era el día en el que los más pequeños nos convertíamos en “hombrecillos en prácticas” porque la buena posición económica que nos proporcionaban las propinas, y los cigarros que intentábamos fumarnos hechos con papel de estraza y rellenos de matalauva, nos hacían sentir importantes. Digo bien al decir “intentábamos” porque aquello que aspirábamos nos producía una tos que nos imposibilitaba seguir aspirando de aquel cigarro infernal, que bien podría recibir el nombre de “sustancia nociva”. Como es lógico, se nos negaba la copa de anís pero, de manera furtiva, “disfrutábamos” o, mejor dicho, sufríamos aquel cochambroso cigarro. Todo fuera por la hombría de unos minutos.

Con el despiece de jamones, paletillas, lomo, espinazo…, concluía la matanza a la que en muchas ocasiones se le ponía fin definitivamente con un “arroz por dentro” o una olla de col, ya sentados a la mesa: de uno u otro plato daban buena cuenta los participantes de tan laboriosa faena.

(Mi agradecimiento a D. Pedro Contreras Salas por la información facilitada; sin ella, buen número de los datos que aquí narro no habría podido aportarlos)

Vera, 11-11-2024

Gabriel Flores Garrido

LA MATANZA DEL CERDO. (THE SLAUGHTER OF THE PIG.)

GABRIEL FLORES GARRIDO

“To those who saw it, but have forgotten it; to those who could not witness it, but are curious to know what it would be like and to those who will no longer be able to know it because it is no longer used or prohibited”

GABRIEL FLORES GARRIDO

Official Chronicler of Vera

I don’t know of any animal that, like the pig, arouses so much controversy when it comes to deciding whether or not it should be treated as food. On the one hand, for Western civilization, its meat and entrails are almost an object of veneration, to the point of being treated as a «food delicacy.» However, Eastern culture, especially Jews and Muslims, prohibit their consumption and, in many cases, even feel rejection for touching them, considering them an impure animal. If we were to establish a food segment, we could place its meat at the two extremes: on one side there would be those who claim that pigs can be used «even their gait» (perhaps referring to their hooves, the protagonists of exquisite dishes) and, on the other, those who do not want to have any contact because of the relationship they establish between the animal and the contaminated and murky character they attribute to it.

– Monument to the Pig in La Alberca, Salamanca –

In this commentary or chronicle we will discuss what affects us most closely and, therefore, is closest to our customs and culture.

Perhaps many of those who have begun to read this “pig chronicle” will wonder why. The reason is none other than the dates we are living in; it is true that in this month of November there are two other events of great significance that could be dealt with in important chronicles: one of a general nature such as All Saints’ Day, in addition to the dedication and remembrance of our deceased, and another of a more local scope such as the destruction of Vera by the devastating earthquake of November 9, 1518; both have been talked about at length and at length, so I have opted for an image and custom that are already lost and from which, in addition, I will try to remember and learn, although I hope that nostalgia does not harm my spirit or that of those who lived through those already lost moments, and that these lines will force them to look back to a point that is already so far away.

St. Martin’s Day (November 11th) has always been considered the opening of the pig slaughter season, although it depended on the area and, especially, on how cold it was and how long the low temperatures lasted. Pigs had been fattened up all year long so that they would be family food for a long time; in fact, there are numerous proverbs referring to the date, including one of them: «every pig has its St. Martin’s Day», with a malicious double intention that everyone knows how to unfold depending on who they are talking to and the reason at that moment.

It is true that sometimes a reason for joy and celebration for some is a misfortune for others; I think that the slaughter of the pig is one of the clearest examples.

I remember the days of slaughter as something extraordinary, very different from the rest of the year. The day began early with the men who were going to participate in the “slaughter” around a bottle of anise, to have a drink that was already part of the ritual and seemed essential before rolling up their sleeves to begin the rite.

– Butcher’s knife owned by Pedro Contreras Salas. Early 20th century –

Not many minutes had passed before the pig’s grunting could be heard as it tried to escape from the hands that, like pincers, grabbed it by any part of its body in order to lift it onto the table and, once on top, tie it up so that the butcher could do his job more comfortably and safely, although I don’t think the poor animal cared much about either one thing or the other, and if they had had the capacity to think, they certainly wouldn’t have spent a second trying to make the job easier for the person who was going to slaughter it. Vera has had good and accurate butchers; it’s not something to boast about, but if we look at it from the point of view that whoever was grunting on that table was going to serve to alleviate the food needs of a good number of countrymen, we would probably see it from a different perspective.

Until then, the pig had lived a placid life: eating, sleeping and eating again was its life cycle.

– Morillo. Our protagonist –

In a house on the lower part of Calle de la Plata my family fattened some pigs that my father almost “humanized” to the point of giving them names. I remember with special “humor and tenderness” “Felipe” and “Morillo”; I don’t know why they had their names, but, in addition to having their own names, he would take them for a walk along the lower part of the street and walk with them to where the Santander bank is today. There he would chat for a while with “Uncle Juan”, a guard who was on the property that is today the Alcaná housing estate, while the pigs patiently sniffed the ground until, once the conversation between my father and the guard was over, they would slowly return home. We will use “Morillo” as the sad and sacrificed protagonist of this chronicle.

As I say, for about a year, if my memory serves me right, everything was placid, happy and a good life for the piglets; so good was it for them that, on occasions, they reached 200 kilos or even exceeded that.

Approximately two weeks before, the spices or “recao” were bought, a term that I did not know; this was the name given to the mixture of paprika, thyme, etc. that had to be cleaned beforehand because they usually came with small stones, which were hidden with the spice itself to increase its weight and thus make a greater profit from its sale. The Spanish picaresque is always present.

When the day of the slaughter arrived, everything was very different for the pig, its pleasant life was coming to an end: the aforementioned table was placed in the middle of the street. Four or five men, once they had caught “Morillo” (to whom we have already assigned the role of “main actor”), held him tightly by the tail, another by the snout once tied to avoid bites, and two others by some of the legs, ears or wherever they could grab onto. It was not an easy task because the animal fought, kicked and thrashed around vigorously trying to free itself from what it seemed to suspect. Its agitation increased in intensity and strength when it felt the knife at its throat and, shortly after, the kicking began to diminish as the blood flowed from its neck and was collected in a basin while they stirred it slowly, thus preventing it from curdling and forming a skein, as they called the strands that formed. The collected blood was used to stuff blood sausages and sausages. There was a belief that if this task of stirring the blood was carried out by women who were menstruating, not only the blood sausages but the entire slaughter would be ruined.

– Scalding the pig. Image by Helios. Property of Sebita Flores. –

Those minutes, which today seem to us, and are, of a cruelty beyond all doubt, were witnessed by a row of children who, sitting on the sidewalk, watched in astonishment, I imagine due to a mixture of fear and surprise, with their eyes open without blinking, and without looking anywhere but the inert body of the poor animal, which was being scalded with boiling water so that, once shaved, the bark of its skin could be used. I suppose that if we children had any capacity for surprise left, we would lose it when we saw the poor animal being scalded by putting us on its skin (this expression will rarely be better used); although, on the other hand, it could not matter much to “Morillo” now that he was doused with boiling water, his suffering was already over.

The pig was hung upside down from a crossbar made of olive wood, usually called a «camal», which was held in place by what in human anatomy would correspond to the Achilles tendon. In this position, its belly was opened to extract viscera, guts and other remains, because everything is used in the anatomy of a pig. Samples of its meat were taken from different points of its body, which the veterinarian analysed in order to avoid the transmission of some disease, especially trichinosis, which, although not inevitably fatal, can sometimes be. The taking of samples and their analysis gave rise to thieving, especially in slaughters carried out in farmhouses and remote places, where the fact did not come to the attention of the veterinarian: there was always the occasional scoundrel who threatened to tell if he did not receive compensation (again, Spanish roguery put into practice).

The fat that «lined» the inside of its belly was removed and separated with a cane, leaving the animal open, avoiding contact with each other to prevent them from acquiring a characteristic odor that would be unpleasant.

Before the tasting was distributed, the sausages had been stuffed: the blood sausages were cooked in a cauldron, previously polished with sand, and placed on a trivet, which in this area we called estrebes, due to the deformation of the word (something that we frequently do in our land).

The next day, very early in the morning, and after the corresponding glass of anise, they proceeded to cut up the poor «Morillo», who had remained hanging from the slaughterhouse all night waiting to be converted into food for several months, although the duration, logically, depended on the number of members of the family.

This second day was a symbol of the slaughter and one of the most anticipated moments: THE MIGAS. In a gigantic frying pan, the flour was constantly stirred until it was well crumbled, opening a hole in the centre to house the “tropezones” (fried bacon, liver and blood sausage cut into pieces, peppers and pieces of lean meat) that were covered and mixed with the migas, recovering the heat they had lost while waiting. From there, like a round table, everyone was ready to, adding a touch of humour, “put the spoon in and take a step back”, as the phrase was coined; if this condition was not met, there was such a number of diners that, despite the large size of the pan, not everyone would have been able to get close to the heat of the migas and the flavour of the trompones.

Another unavoidable moment of the slaughter was the distribution of the sample offered to friends and relatives, which generally consisted of a piece of bacon, a couple of blood sausages and a spine bone; we, the youngest, were in charge of this, and we always showed interest in handing out the samples because, frequently, it was rewarded with a few pesetas, which always came in handy. Another unavoidable moment of the slaughter was the distribution of the sample offered to friends and relatives, which generally consisted of a piece of bacon, a couple of blood sausages and a spine bone; we, the youngest, were in charge of this, and we always showed interest in handing out the samples because, frequently, it was rewarded with a few pesetas, which always came in handy.

It was the day when we, the youngest, became “little men in training” because the good economic position that the tips provided us, and the cigarettes that we tried to smoke made of brown paper and filled with matalauva, made us feel important. I say “tried” because what we were inhaling made us cough, making it impossible for us to continue inhaling that infernal cigarette, which could well be called a “noxious substance”. Naturally, we were denied the glass of aniseed, but, in a furtive way, we “enjoyed” or, better said, suffered that filthy cigarette. Anything for the manliness of a few minutes.

With the cutting up of hams, shoulders, loins, spines, etc., the slaughter concluded, which on many occasions was definitively ended with a “rice inside” or a pot of cabbage, already seated at the table: the participants of such a laborious task thoroughly enjoyed one or another dish.

(My thanks to Mr. Pedro Contreras Salas for the information provided; without it, I would not have been able to provide much of the data I describe here)